Over the years, Randolph-Macon Woman's College students and faculty have traveled the world on a variety of travel seminars. Locations include:

Bali, China, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, India, Japan, Russia, Senegal, and Tunisia.

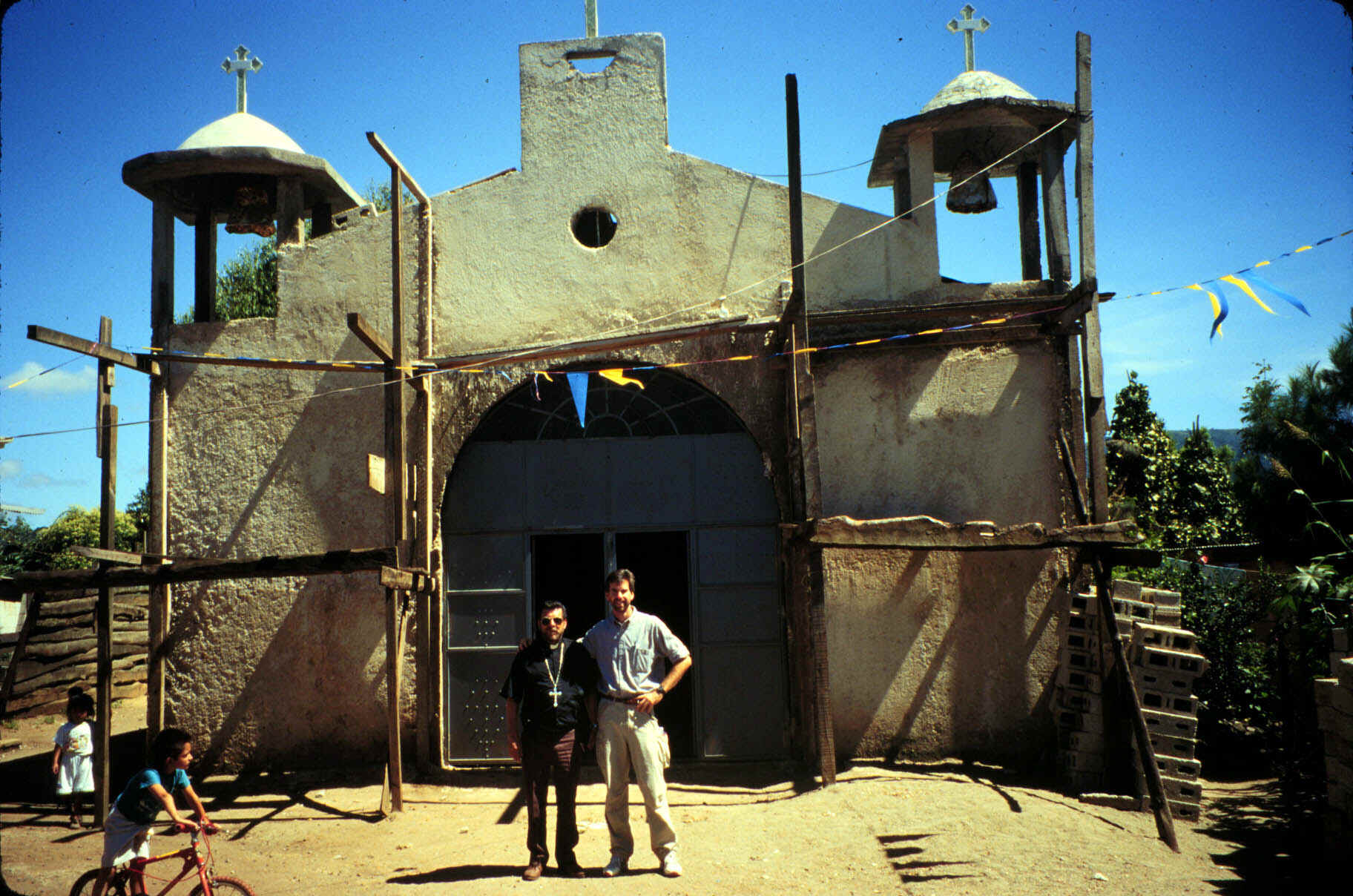

In June 1997, 8 R-MWC students and I, along with 9 other participants (a total of 18) traveled to Guatemala and El Salvador to study issues of peace, justice and sustainable development. The trip was formally titled: Sustainable Development and Peace in Guatemala and El Salvador: Comparisons, Contrasts, Lessons. Here is our group, along with Padre Horacio Castillo and some neighborhood kids in front of the (all purpose) community building in La Isla, Guatemala, a marginal community on the outskirts of the capital, Guatemala City:

Pictured above: Top row standing, left to right: Padre Castillo with two neighborhood children in front of him, John Abell (R-MWC), Ruth Bronstein, Tammy Williams (R-MWC alum and former development staffer), Jane Agee (R-MWC), Stephanie Godfey (R-MWC), Allen Pritchard (Tammy's husband and former R-MWC admissions staffer), Joshua Peters, Amy Withers (R-MWC alum and Guatemala Peace Corps volunteer), Kathryn Stewart, Kimberly Wick (Center for Global Education trip leader), Heather Hoffman (R-MWC).

Bottom row kneeling left to right: Jody Halsall, Nancy McAndrew (R-MWC), Kathleen Hatfield, Holcomb Pittman (R-MWC), Liz Bolduc, Tressa Gandy (R-MWC), Rev. Dick Blomker.

The idea for this trip originated with a simple suggestion from one of my students years ago, long before I had even traveled to this part of the world. I had been talking in class one day about issues of peace and justice in the context of Reagan's war against Central America. The student, whose name I have long forgotten, suggested to me that I ought to organize a trip with students to Central America so we could check out all these issues on our own. Approximately 10 years later, after much travel, study, and planning, the trip described here resulted.

Central America is not the safest region in the world in which to plan a trip. El Salvador had signed its peace accords in 1992 ending a decade of violent conflict. The decade of violence began with the outrageous murder of Archbishop Oscar Romero on March 24, 1980, peaked on November 16, 1989 with assassination of 6 Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter on the campus of the University of Central America before exhaustion of the warring parties led to the signing of the accords in Chapultepec, Mexico on January 16, 1992. At the time of our travels, the ink was barely dry on Guatemala's accords (completed in December 1996), bringing to an end nearly 4 decades of brutal civil war in that country that had resulted in over 200,000 dead or disappeared, nearly 2 million displaced from their homes and villages and over 600 villages wiped off the map.

Because of such safety concerns, we made use of the services of the Center for Global Education of Augsburg College in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Center has been organizing trips to Central America since 1983 at the height of the Contra War against Nicaragua. It was felt that Americans could formulate their opinions about this particular controversial war and other aspects of US foreign policy in the region by traveling directly to the region and seeing things first hand--meeting with the affect parties, experiencing the culture, eating the food, staying in the countryside, and so on.

I came up with the kind of trip I wanted our students to experience, including a long list of specific people and places, and the Center then made it all possible, both through their staff in Minneapolis and through their in-country staff in both countries. It was the in-country staff who had the responsibility to organize meetings, places to eat and sleep, and other travel logistics.

There was a Spring Semester course required of all student participants. It was a general (100-level) course open to all students (including those not going on the trip) that examined issues of peace, justice, access to land, economic development, sustainable development, history, religion, the military, indigenous peoples, and women's issues. The course was titled, The Western Development Model: Lessons from Guatemala and El Salvador. The syllabus for that course may be found at the following site: Spring 97 Course.

The trip itself had a syllabus which you may peruse at the following site: Travel Seminar 97. An excerpt from that syllabus provides the flavor of what our trip was about:

"The central focus of the travel seminar to Guatemala and El Salvador will be an examination of alternative development models. Development is meant in a comprehensive sense and includes economic, political, environmental, social, cultural, and religious development. The trip will represent an opportunity to observe first-hand the nature and extent of development that Guatemala and El Salvador have experienced following 500 years of Western influence. Development is likely to occur in a different manner in a country that is at peace than in one that is in a state of war. As the decades long war in Guatemala winds down, are there useful lessons to be learned from El Salvador's five year experiment with peace? An equally important focus is on the role of women in the development process in these two countries. What conditions must exist for women to break out of the traditional roles that have been in place for centuries? We will have a number of opportunities to visit communities where the tension between these traditional roles and more progressive roles for women are quite evident."

Click out the following link for a look at our rigorous itinerary.

Images from the trip:

Guatemala:

The group photo above was taken in front of the community center in La Isla, on the outskirts of the capital city. The Center is one of only two permanent structures in this isolated community. The other is the new concrete church in the picture below.

Permanent structures such as these represent both progress and hope for this community of refugees from the civil war. Over the years, as the conflict displaced hundreds of thousands of people, they had the following choices: flee to Mexico, flee into the mountains and jungles of Guatemala, or flee to the capital city in hopes of finding employment and starting new lives. The people of La Isla chose the latter. Unfortunately, for the many communities like them who settled on unused parcels of land on the outskirts of the city, their communities are an eyesore to the city fathers, who want the world to have a better image of Guatemala than one of impoverished refugees. So frequently, in the middle of the night, the military will forcibly remove such citizens, bulldozing their hastily assembled buildings into a nearby ravine.

Having permanent structures makes such actions less likely. La Isla has somehow survived due to the impressive organizing abilities of the community, especially the women, as well as from the assistance of Padre Horacio and the international community which has stood beside the community every time the military and the corrupt court system has attempted to evict them. Every year that passes without eviction increases the chances of more permanent residence. They now have electricity instead of having to operate lights using old car batteries. They now have potable water outlets as seen in the photo below, instead of having to walk nearly 5 miles into town to the nearest source.

Visiting La Isla and sharing a meal that community members had prepared for us and listening to their stories was an eye opener for our group. This all took place on day #1.

Another important visit in Guatemala was to the community of San Lucas Tolimán in the highlands. This is a community of about 40,000 nestled on the southeast shore of Lake Atítlan. The city proper has about 20,000 and another 20,000 are settled in a number of outlying aldeas.

I have contributed a chapter on San Lucas Tolimán to a volume on the Economics of Conflict and Peace entitled: Peace in Guatemala: The Story of San Lucas Tolimán. It can be read in its entirety at the following site: SLT.

The community has a strong relationship with the Catholic diocese of New Ulm, Minnesota in the states. Forty years ago, the parish established a sister relationship with San Lucas and sent a young priest by the name of Greg Schaffer who thought he might be staying only for a month or so as a temporary replacement.

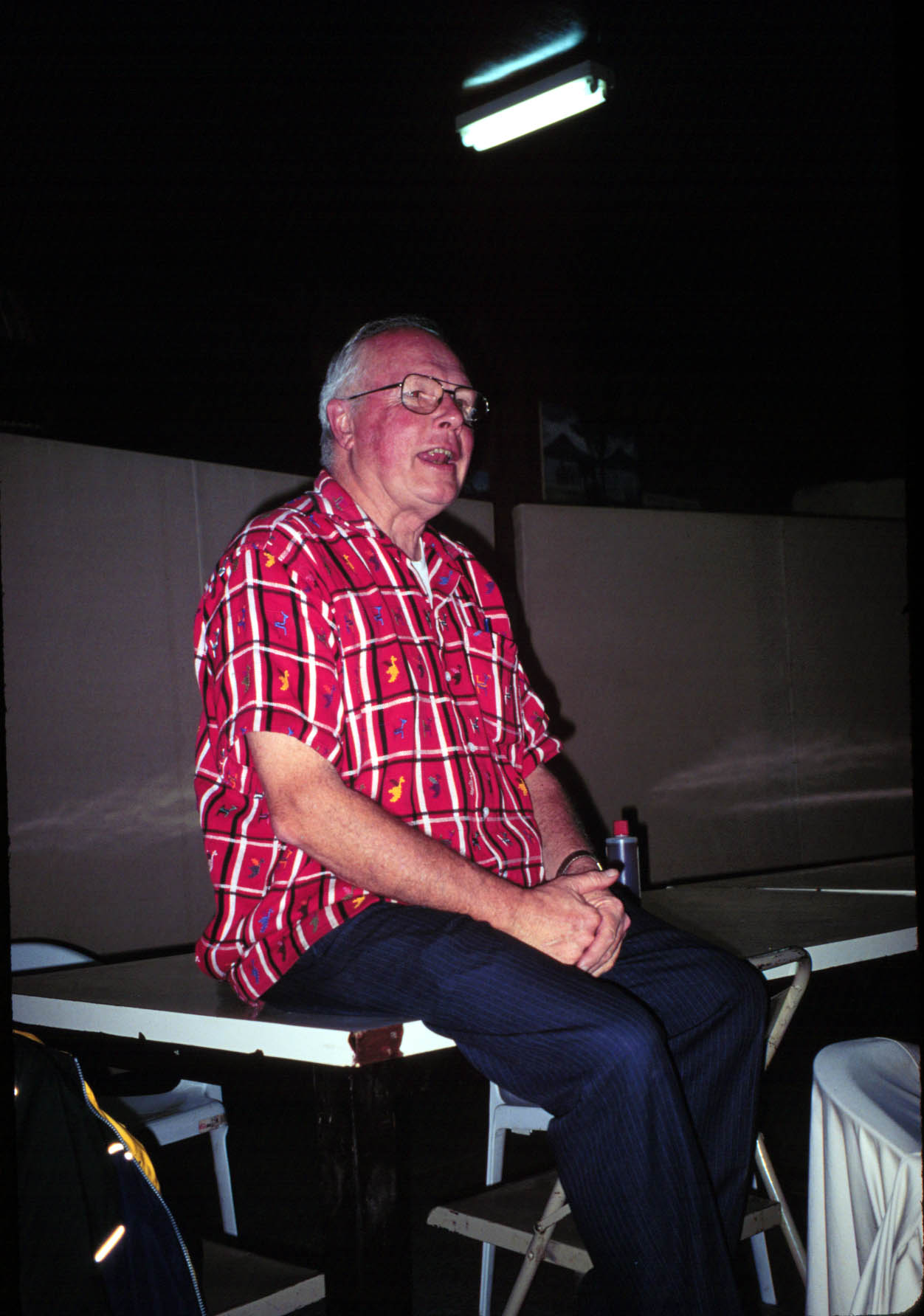

Padre Greg giving his famous Process of Poverty talk to our group

As things turned out, his stay became permanent and he was forced to cope with a situation which seminary had ill-prepared him for: a terribly impoverished community in the middle of what was about to become a civil war zone. He forged ahead helping the local parishioners to expand the church's offerings, including education and health care, and later expanding the parish's programs to include a coffee project, honey bee project, permaculture farm, reforestation project, home construction program loosely based on Habitat for Humanity's structure, and most importantly, a land acquisition project. Not often, but occasionally, a parcel of land will come up for sale in the middle of some of the most valuable coffee land in the entire world. When possible, the parish places a competitive bid and when successful makes the land available to the citizens of San Lucas in 3 acre lots. This land program is making a significant improvement in what has been the most vexing problem facing Guatemala and many other poor countries--a terribly skewed distribution of land.

A tour of San Lucas gave our group a close-up look at what sustainable development is all about.

These workers are cutting bamboo trunks for use in the Parish-supported regional hospital. We were told that bamboo is as structurally sound as 2x4s, but has the advantage of being grown locally and available for free. Wherever possible, parish projects make us of local labor and materials so that the various economic multiplier effects take place within the community.

Weigh-in for participants in the parish coffee-buying program. The parish pays these families 200 Quetzals (approximately $14) per quintal (100 hundred pounds), which is significantly more than what the regular coffee market would bear. The parish then processes the coffee locally and sells it through its distribution system out of New Ulm. By the way, each of the bags these men are carrying weighs approximately 130 lbs!

Another memorable visit we made was to the Ruth and Naomi project in Chichicastenango. We had first heard about this project from one of the founders, Jauna Chicoj, who was in the states during the previous spring semester and spoke to our class. The project is multi-faceted. A primary goal is to provide jobs (and skills training), health care (making use of native medicinal plants), and an agriculture base of support to the indigenous population which is still suffering from the effects of war. Here, Tammy and Allen are working with Juana and a helper on one of the community's farms. We all definitely learned the meaning of WORK that day!

El Salvador:

Where ever we went in El Salvador, from the U.S. Embassy in San Salvador to the remote mountains of Morazon, the issue of human rights was never far below the surface. It will take generations of healing to erase the troubling memories of the decade-long civil war. The Moviemiento de Mujeres (Women's movement) is at the cutting edge of the human rights movement in the country--from fighting for information on disappeared loved ones to fighting for respect and a living wage in the maquiladoras. The group pictured below is called Melida Anaya Montes (MAM). Their stories were both inspiring and disturbing. They confirmed every tale of abuse that one has ever heard about conditions for working women in the sweatshops of Central America.

A visit to the campus of the Jesuit University (University of Central America) provided us with stark images of the brutality of the civil war. It was a chilling experience to stand in the street and look down the line of rifle sight into the campus's hospital (Divina Providencia) chapel that Monseñor Romero's assassin would have had on March 24, 1980. Likewise it was an unforgettable visit to the Romero memorial museum which is located on the grounds where the Jesuit priests were assassinated on November 11, 1989.

Jane Agee stands in front of the memorial chapel. The inscription refers to Monseñor Romero and says, "If they kill me, I will be resurrected in the Salvadoran people."

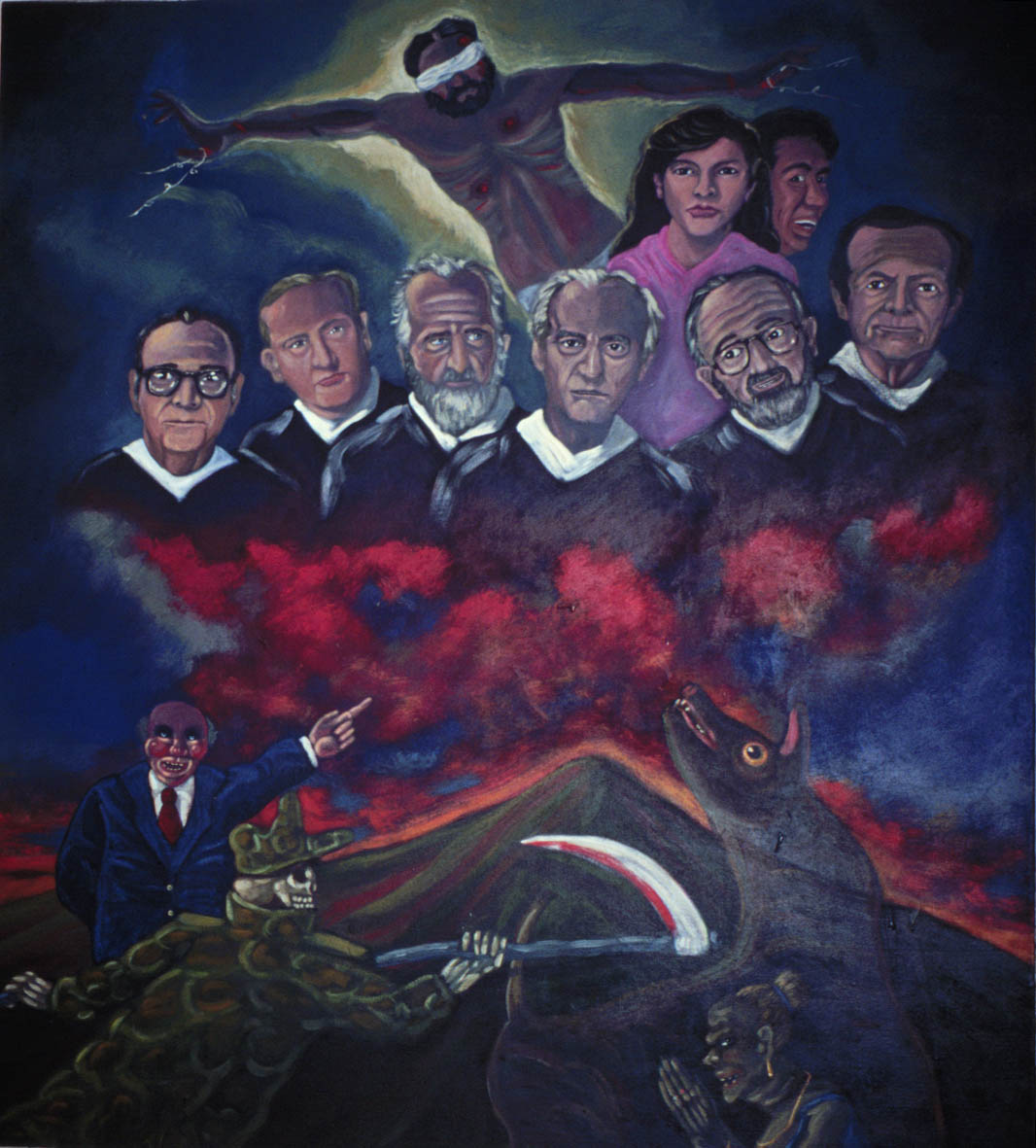

The painting inside the memorial chapel depicts the evil associated with the assassination of the Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter by the Salvadoran military. The third Priest from the left, Segundo Montes, played a significant role in the lives of the people on one of our next visits--to a city named for him high in the mountains of Morazon.

Cuidad Segundo Montes is a community of returned Salvadorans from the refugee camp at Colomoncagua, Honduras. They spent the majority of the decade of the 1980s there in fear of reprisals from the Salvadoran army. They had originally fled their community of Meanaguera in the face of a military sweep through the region in November 1981. In early 1990, well before the 1992 signing of the peace accords, the community began its return to El Salvador to re-establish itself on an empty plot of land they named for the priest who had helped them during their period of struggle in Honduras.

The photo is of one of the schools the community erected immediately upon its return. The girls are singing a song for us. During their time in Honduras, education became a priority. Theoretically, education is available to all children in El Salvador. In practice, it is still pretty much a privilege of the rich. Cuidad Segundo Montes is trying to address this deficiency with educational opportunities for students of all ages.

There is even a community band, El Conjunto de Morazon. Pay attention; they occasionally appear in the United States when there are various benefit concerts in locations like Washington DC.

Check out Jane and Liz rockin down to the smooth sounds!

Just a few miles up the road from Cuidad Segundo Montes is the site of the worst massacre of the war: El Mozoté. Approximate 1200 villagers died when the military swept through the area (in the same action that caused the citizens of Meanguera to flee to Honduras). Their names are listed on the wooden plaques in this memorial. A single individual, Rufina Anaya, escaped to tell the story of the massacre. You can read the account of this horrible event in the Dec. 6, 1993 New Yorker Magazine. The entire issue is devoted to the story.

Needless to say, with all of the memorials to violence, El Salvador gave us many things upon which to reflect. That the country remains at peace after the atrocities of the 1980s is nothing short of a miracle. That the guerrilla forces of the FMLN (Farabundo Marti National Liberation force) laid down their arms, formed a political party, and today hold approximately 1/2 of the seats of the Salvadoran national legislature is testament to the heroic efforts of the people of El Salvador to reconcile their differences and forge a new and hopefully more just and prosperous future.